TACTICAL ANALYSIS: Understanding the Mwalala magic at Bandari FC

Reading Time: 6min | Sat. 31.01.26. | 10:40

The Mombasa-based side's recent sequence against strong opponents - Tusker (2-1 away win), Kariobangi Sharks (0-0 draw), and Kenya Police (1-0 home victory) - reveals a clear tactical fingerprint taking root under the tactician showing why Kenya Police FC, AFC Leopards were after his signature and Shabana were desperate to keep him

Bandari FC are riding a wave of momentum under Bernard Mwalala, extending an impressive unbeaten run to seven games as they prepare to face Shabana FC this Sunday, 1 February in Kisii.

The fixture carries extra narrative weight: Mwalala, who recently returned to the Dockers after an impactful stint as assistant at Shabana, now travels to confront his former employers with Bandari showing renewed purpose and tactical cohesion.

Follow Our WhatsApp channel for more news

Bandari’s recent sequence against strong opponents - Tusker (2-1 away win), Kariobangi Sharks (0-0 draw), and Kenya Police (1-0 home victory) - reveals a clear tactical fingerprint taking root under Mwalala.

Despite varying scorelines, the underlying patterns remain remarkably consistent: a goalkeeper-initiated build-up, pronounced right-sided attacking emphasis, and a high-intensity counter-pressing system that repeatedly dictates match tempo and territory.

This tactical dissection examines how these elements - base formations, progression mechanics, pressing triggers, and defensive vulnerabilities - have tilted games in Bandari’s favour, while highlighting the structural risks that persist in their organisation.

By unpacking these layers, the analysis shows not only what the Dockers are executing, but precisely why their approach is proving so effective in the Sportpesa Premier League.

Across the three matches, Bandari’s nominal starting structures shifted between a 4-2-3-1, 4-2-4 and 4-4-2 depending on personnel and opponent.

However, these formations served only as reference points. In possession, Bandari regularly morphed into asymmetric attacking shapes - most notably a 3-2-4-1 or 3-2-5 - while out of possession they alternated between a 4-4-2 and 4-1-4-1 mid-block.

Crucially, roles defined behaviour more than positions. Centre-backs Shariff Majabe and Andrew Juma were not passive defenders but primary progression tools.

Pivot Said Tsuma frequently vacated midfield zones to drop into the first line, enabling full-backs to advance. Wingers were tasked with extreme verticality in attack but deep recovery runs out of possession.

These relationships, rather than the listed formation, governed Bandari’s spacing and control.

Before assessing Bandari’s attacking success, it is important to understand the defensive logic of their opponents. Tusker and Kenya Police largely defended in compact mid-blocks with man-oriented tendencies around the ball, while Kariobangi Sharks attempted to compress vertical space using a higher defensive line and aggressive stepping from centre-backs.

What united all three opponents was a prioritization of central compactness. This inevitably left the wide corridors as pressure-release zones most of the time - areas Bandari were structurally prepared to exploit.

Each opponent sought to deny central progression first, but in doing so repeatedly exposed the same weaknesses once forced to shift laterally.

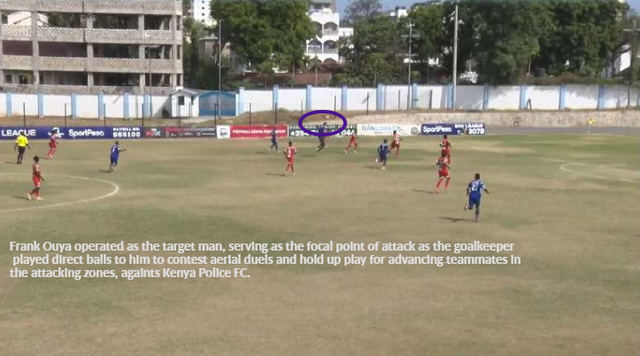

Bandari’s build-up consistently began with goalkeeper Allaine Ngeleka acting as an active outfield player rather than a safety valve. Instead of remaining anchored to his penalty area, Ngeleka routinely stepped between or beyond his centre-backs, creating a situational back three and numerical superiority in the first phase.

This structure served two key purposes.

First, it baited the opposition press, inviting pressure centrally before releasing the ball diagonally. Second, it allowed Majabe - particularly on the right - to receive on his preferred foot with time and a wide passing lane. From here, long diagonals toward the right wing or vertical passes into the striker’s channel became Bandari’s primary progression method.

The build-up was deliberately low-risk yet direct: circulate to draw pressure, then bypass midfield lines with purpose. Against Tusker and Police, this approach repeatedly disrupted pressing cues and forced defenders to retreat at speed.

Bandari’s rotations were subtle but effective. Tsuma’s repeated drops into the defensive line were not merely about ball security; they triggered chain reactions.

When Tsuma dropped, full-backs advanced. When full-backs advanced, wide defenders were pinned. This allowed interior midfielders and wingers to operate between lines or receive on the half-turn.

On the right, this rotation was especially pronounced. Darius Msagha’s explosive positioning forced opponents into binary choices: step out and leave space behind, or hold shape and allow him to receive facing forward.

Either option benefitted Bandari. In several sequences against Tusker, Msagha’s ball-carrying forced second-line defenders to jump, creating second-ball opportunities - one of which attacking midfielder Geoffrey Ojunga converted by attacking the loose ball centrally.

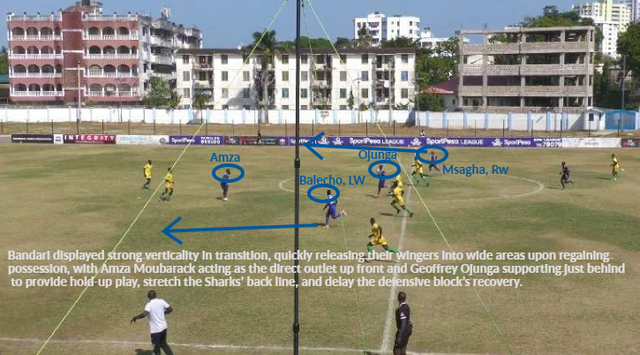

A recurring theme across all three matches was Bandari’s commitment to right-sided progression. This was not incidental.

By repeatedly building through Majabe, the right back - Joseph Ouma and targeting Msagha early, Bandari overloaded the opponent’s left defensive channel before the block could shift horizontally.

This approach exploited two weaknesses simultaneously: slow lateral shifting and poor rest-defence balance.

Once the ball travelled quickly from central build-up to wide attack, opponents were often left defending while moving backwards - a scenario Bandari used to generate second balls, cutbacks, and broken defensive structures rather than clean chances.

Even when initial attacks broke down, Bandari’s positioning ensured they were first to loose balls, sustaining pressure without reckless commitment.

Rather than forcing play through congested central zones, Bandari used width as a manipulation tool. By stretching the opposition horizontally, they created pockets of space in advanced half-spaces, particularly for second runners.

Against Tusker, the equaliser conceded paradoxically highlighted this strength: Bandari had drawn Tusker’s block so wide that recovery tracking failed on a delayed box run.

While this moment exposed defensive concentration issues, it also underscored how effectively Bandari had destabilised the opponent’s shape.

The consistent pattern was clear: wide occupation → horizontal stretching → delayed central access.

Out of possession, Bandari adopted an assertive counterpressing model. Upon losing the ball, the nearest players stepped out immediately to delay the opponent rather than dive into challenges.

This approach prioritised space control over ball recovery, buying time for the block to reset.

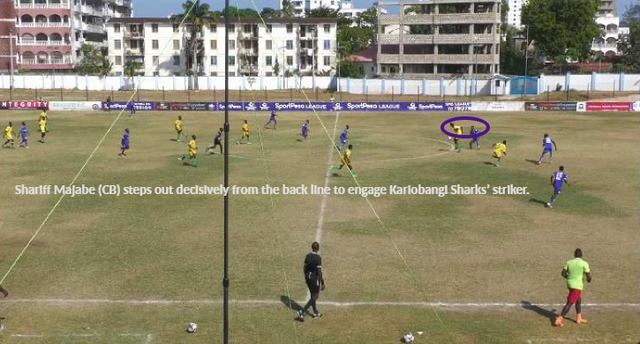

Their pressing shape typically resembled a 4-4-2, with one striker engaging the ball carrier and the other screening central passes. Curved runs forced play toward the flanks, where touchline pressure traps were activated. Against Sharks in particular, this resulted in frequent aerial duels and contested second balls - areas where Andrew Juma’s aggression and timing proved decisive.

Bandari’s rest-defence was one of the most consistent elements across the three matches. Even when committing numbers forward, at least three players remained positioned behind the ball, close enough to engage immediately after loss.

This proximity allowed Bandari to compress vertical space rapidly, preventing clean counter-attacking lanes.

Rather than retreating passively, centre-backs - especially Juma - stepped aggressively into midfield zones to intercept or force rushed decisions.

This proactive approach limited opposition transitions, particularly against Sharks, who struggled to exploit Bandari’s high line despite repeated attempts.

Bandari showed adaptability when faced with new threats. Against Kenya Police, aggressive centre-back stepping began to expose space behind the left-back, where Malonga repeatedly attacked vacated channels.

While this created moments of danger, Bandari responded by staggering their stepping triggers and allowing one striker to drop deeper while the other pinned the back line.

This adjustment reduced exposure without abandoning their core principles. Importantly, it reflected game-state awareness: Bandari accepted slightly deeper defensive positioning in exchange for control during key phases.

In sustained defensive phases, Bandari maintained compact horizontal spacing but occasionally lost individual references inside the box.

The Tusker equaliser, stemming from a long throw and late runner, highlighted lapses in man-tracking rather than systemic collapse.

Still, the overall defensive picture remained coherent. Wingers recovered diligently, the back line stepped in unison, and aerial dominance - particularly through Juma - helped neutralise sustained pressure.

Defensive discipline, while not flawless, aligned with the team’s proactive identity.

Across these three matches, Mwalala’s Bandari FC demonstrated a well-defined tactical DNA built on goalkeeper-led build-up, vertical progression, right-sided attacking emphasis and aggressive counterpressing.

Their ability to control matches without much ball possession speaks to structural clarity rather than improvisation.

The trade-offs - exposure behind stepping defenders, lapses in box marking - are inherent risks within their proactive model rather than signs of instability.

With improved defensive communication and slightly refined timing in their stepping triggers, Bandari’s system shows strong potential for sustained success.

Ultimately, Bandari’s performances were not defined by moments, but by patterns - and that is the hallmark of a team with a growing tactical identity.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)